Every year since 1998, museum in progress has transformed the safety curtain in the Vienna Opera House into a gigantic piece of art. Each year a jury selects an internationally regarded artist to create its new image, which is installed with magnets onto a screen, creating an ever-changing exhibition space lasting one season each. Only the dimensions remain the same. Indeed, one of the most striking aspects of ‘Safety Curtain’, and the only shared quality across all twenty-seven iterations, is its incredible scale: one hundred and seventy-six square metres, the pictures loom large over the audience.

One of the many interesting aspects of this project is the way the Curtain enmeshes utility with spectacle, in a daring and avant-garde project to bring art directly to audiences. Where else is art viewed in this manner, with an audience sitting facing a painting? Perhaps only an auction. But museum in progress is not a commercial venture. Staging a painting in this way decontextualises art from commerciality— the Curtains are hung without a price. What I find most interesting about this project is the implications of staging a painting: it reaches towards a gesamtkunstwerk (a total work of art, ‘collated into one interrelated subject, project and study, so that an overarching design schema would cover all elements of a creation’)1: by identifying a gap, a possible site of representation, as many faces of the space are being utilised as possible, creating a multitudinous experience. An opera is itself already a multi-media piece of art— a phenomenon which comprises performance, set, music and so on— of sound and image. By incorporating the space itself into the reception of the opera house, as Robert Fleck points out, the curtain is ‘brought into a state of dynamic change’.2. The various facets of the Weiner Staatsoper, as a gesamtkunstwerk, are transposed to form different ways of reading the space, remaking the opera house into a dynamic museum space. In one possible way of reading this, and the way I personally see it, “Safety Curtain” transforms the Vienna State Opera House into a gigantic picture frame.

Below are some of my favourite versions from its twenty-seven year history.

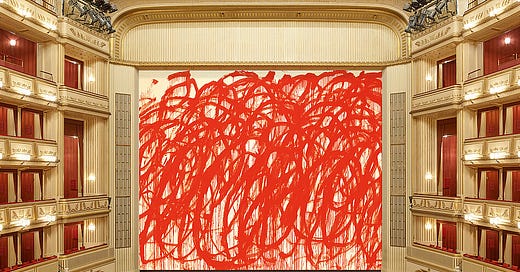

Cy Twombly, Bacchus, 2010-2011

credit: museum in progress

Of the twenty-seven, Cy Twombly’s is my personal favourite. It is magnificent. Its incredible grandeur is a compellingly different flavour to the grandeur which surrounds it; the simplicity of the use of one uniform colour, red on white, in cahoots with the traditional interior of the Wiener Staatsoper whilst simultaneously clashing with its opulence is arrestingly striking. There is, of course, something disconcerting about it: that shocking arterial red is bracingly provocative, and those enormous, sweeping loops in a fury of expression, evoking the spilling of blood. But where else more befitting than on an opera stage? I looked up the programme for that year. The season included Medea, Salome, Romeo and Juliet, Elektra. Massacres, suicides, murders, beheadings. Marvellous. Expressionism finding its stage both in Twombly’s safety curtain and the operas it rose to reveal. In Bacchus in particular, I find there is something which satisfies the Artaudian total theatre in its histrionism. In my view, the overwhelm Artaud sought, the theatre-as-plague wherein the hidden but spectacular force of artistic reception could powerfully disperse, is manifested in particular by Bacchus. When an audience is typically at rest— prior to a performance, during the interval, and when the curtain comes down— they are confronted with this towering spurt of blood.3

credit: Wiener Staatsoper

Another angle of Bacchus. Here you can see how the curtain is at once in harmony with the rest of the theatre and a bold departure from it. The resultant clang of colour and form, the use of flatness in a round room, as well as its brazen quality is a perfect example of what the Curtain enables: polarising, invigorating experiences of art.

Pipilotti Rist, abdominal cavity flies over a dam, 2024

The selection for this year was Pipilotti Rist. I have a personal affection for Rist— as a teenager I was introduced to her work at the Hauser & Wirth art gallery (who represent her) in Bruton, where I worked as a teenager. She was frequently talked about in the gallery, and by locals whom she had befriended during her residency a few years before. For me, living in rural Somerset growing up, the gallery opened up a portal to an entire world of possibility. I could simply step through and have this incredible proximity to art which typically would have otherwise been beyond my reach. Aside from working as an invigilator on Saturdays and during the holidays, I ended up participating in a number of different projects while I was there, including making a painting with Martin Creed, and shooting a short film which was added to the gallery wall as a suffix to Subodh Gupta’s show Invisible Reality, a show I still think about nearly ten years later. It was an incredibly exciting time in my life, and one which paved the way for me to pursue essentially all of the things I have done in the last decade. Its youth group Arthaus, which I was also a part of, is still going today. That being said, I was delighted to see Rist’s selection for the Curtain for this year.

The otherworldly quality of Rist’s work is perhaps especially present here— the imposition of the organic, an abdominal cavity, in X-ray black-and-white, onto this dreamlike (nightmarish?) landscape of kaleidoscopic colours is another example of a Safety Curtain utilising the discordant to bold effect. The sense of dynamism in this image, the vibrations emanating from the centre, is really compelling. The upper third draws the eye to the valley between the mountains, but the strangeness of the abdominal cavity pulls you into this murky underworld beneath. As with the Twombly, the opulence of the opera house serves as the perfect frame: that cream proscenium arch allowing Rist’s electrifying colours to burn into your eyes.

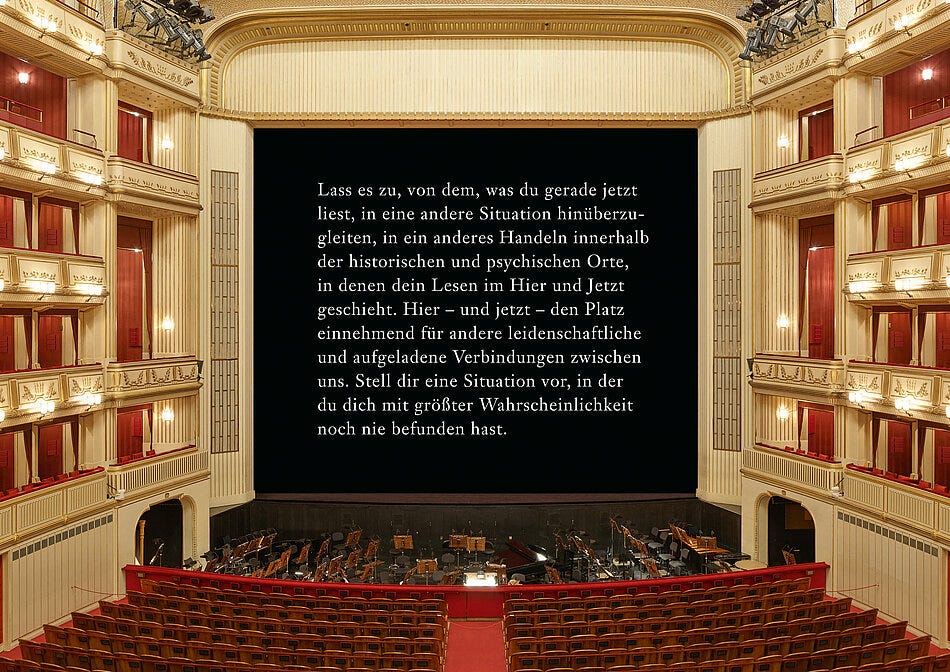

Cerith Wyn Evans, safety curtain, 2011.

I find this one particularly interesting due to the use of text-as-image. Evans is, so far, the only artist to have used only text for his curtain. Some of the previous versions have used words or slogans, for example David Hockney’s cartoonish and whimsical illustration of theatre curtains with the words ‘Wien Musik’ taking centre stage, or Rirkrit Tiravanija’s test pattern colour bars bearing ‘ANGST ESSEN SEELE AUF’ (fear eats the soul), but they have been in dialogue with image, or inseparable from it. Evans’ curtain is simply a manifesto:

"Permit yourself to drift from what you are reading at this very moment into another situation, another way of acting within the historical and psychic geographies in which the event of your own reading is here and now taking place; here, and now taking the place of other ways of making passionate and energetic connections between us. Imagine a situation that, in all likelihood, you've never been in."

Two imperatives open the sentences of Wyn’s piece: permit yourself and imagine. The entire thrust of Wyn’s instructions is to think flexibly. It is in many ways the perfect meditation to undertake prior to watching a performance, to remind oneself to take things in with judgement but not prejudice, to consider your role as an audience member and the importance of that relationship. Of course, the words are also applicable beyond the opera’s walls.

Something I have been thinking a lot about recently is the state of being stranded in history. When imagining how people of the past experienced their own time, and perceived the future in which we are either living or have sailed long past, we are limited to the lens of our own position in time. Wyn’s Curtain urges the audience to reflect on this, the lottery of birth, and to undertake the mental exercise of empathising with people we have never met or may never meet.

Here, as Martin Prinzhorn points out, language ‘conquer[s] the canvas and the image with text and writing’4, creating an image-as-text which can both be read and regarded as an image. Indeed, for those who cannot read German, this safety curtain is an image of text, and all that can be considered is words in place of an expected image. But this reading is influenced by the context of the ‘Safety Curtain’, and an audience member’s expectation of it as an art exhibit, rather than a safety measure.

I should mention, too, that the Vienna State Opera has an annual budget of one hundred million euros, fifty per cent of which is subsidised by the state. The state enables not only this historic opera house to continue to operate at a staggering level, with over three hundred and fifty performances a year, but projects such as this to continue their life cycle. Invigorating art leads to the betterment of people. A society is reformed and improved by access to art and to ideas. It invites them to consider the world they live in and their position in it, as well as to imagine the lives of others, as Wyn Evan’s curtain urges.

Each safety curtain has been boldly different from the last, but each one has pleasingly jarred with its ornate surroundings. Perhaps it is this which I enjoy the most about it— the joy of the unexpected, the collision of the old and the new, the enlivening of public art by placing it on a stage, its disdain for the ossification of institutions. I find its boldness, and its ever-fresh face encouraging, and I hope it goes on, in its changing way, for a long time.

Thank you for reading A Pearl Dissolved in Wine! If you enjoyed reading this, please consider sharing and subscribing. I write personal and cultural essays largely about performance, glamour, and erotics.

Until next time,

— Megan.

Naomi Martin, Gesamtkunstwerk –The Total Work Of Art Through The Ages, Artland Magazine

Robert Fleck, ‘Redesigning the Safety Curtain’, museum in progress, May 1998

Shout out to Frankie Gardner for putting me onto that play.

Martin Prinzhorn, ‘Cerith Wyn Evans, Safety Curtain 2011/2012’, trans. by Jacqueline Csuss, museum in progress, 2011

Liked before even reading ftw