This essay tells the story of a week-long migraine I experienced in February, but it also delves more broadly into the experience of chronic pain without a formal diagnosis. In an irony of ironies, I received a diagnosis the day I completed this essay. For years I have experienced intense, draining pain without knowing where it comes from or how best to treat it, and I now sort of have to laugh at the drawer full of painkillers, muscle balms, roller-balls and medicines I did not interrogate. Apparently it is not normal to acquire analgesics, constantly. It is remarkable what you can normalise to yourself. However, the central concern here is the problem of communication of pain, and I use Virginia Woolf’s On Being Ill and Eula Biss’ The Pain Scale to illustrate this, among others. I hope you enjoy it— I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments below. Please consider subscribing to A Pearl Dissolved in Wine<3 <3 <3

~~~

i. Me, my boyfriend, the friendly axe in my head

I am currently nursing day five of The Headache Which Would Not End. I feel hollowed-out, strange, on the verge of something drastic. This chthonic headache has risen steadily and stealthily, a floe of ice, up into my eyes and now stands tall and grave and unmoving, like a mountain between me and everything else. Snow-capped, the pain itself has a quality of coldness, the same cold rigidity of a chain which fastens me still.

The carceral quality of chronic pain is something I am familiar with. For years I have experienced severe pain of different qualities which I have never been able to diagnose. My policy is simply to still go outside, to still go to things and see the world, lest I become a shut-in, which I spent some time as during the ages of eighteen to twenty. My coming-of-age was characterised by this intensely lonely feeling of watching the world of everyone else, orbiting them from a moon-distance, never to touch ground and feel its warmth. I have since found ways of Being In The World. Sometimes, however, a sudden episode will suck all of the air out of my lungs.

I have entered the morbid phase of prolonged pain wherein you begin to accept that this may be the end. This week has essentially disappeared into a fugue; a long, bourdon note. Time whips above my head like a shrill wind, or sometimes it has weird signatures— syncopated, slow. I have slipped sideways out of time, as I have done many times before. I may be twenty-five, but in the years I have spent in the waters of annihilation, I am far older. Time is different, there. Blue is not blue. Life is lived above the surface. But for deep-sea creatures, there is a surface beneath the sky. It is a wall. Water suspends gravity. Once you sink into it, you can keep going down forever. ‘Clothe yourself, the water is deep.’1

And that is all it takes, as many of us know. So short a time of suffering can smother your entire world. Virginia Woolf illustrates this experience as well as I have ever seen in her 1926 essay On Being Ill. This part from the opening paragraph is so good I will print it in full:

The undiscovered countries that are then disclosed, what wastes and deserts of the soul a slight attack of influenza brings to light, what precipices and lawns sprinkled with bright flowers a little rise of temperature reveals, what ancient and obdurate oaks are uprooted in us in the act of sickness, how we go down into the pit of death and feel the waters of annihilation close above our heads and wake thinking to find ourselves in the presence of the angels and the harpers.2

Most striking in this essay is the way Woolf addresses the limits of language. She points to a ‘poverty of language’ in describing illness— how a teenage girl experiencing falling in love for the first time has Keats, Shakespeare [et al] to call upon, the sweet agonies and ecstasies being diagnosed for her and thereby legitimising her experience. At her time of writing, Woolf points out a dearth of illness as a subject of literature. Now, of course, you can hardly move for fiction populated with pains, diseases, illnesses. If anything, we have gone too far.

But despite this development, to accurately describe pain and its nature evades language; resists it. Indeed, Woolf describes how a patient in front of a doctor must ‘coin words for himself’.3 This reminded me of my own hierarchy of headache severity I invented during a period of chronic headaches as a first year undergraduate. I would very often have to lie down in a dark room with a frozen water bottle strapped to my head; during these times I would listen to Philip Glass or Henryk Górecki and wonder if I might simply slip off my mortal coil. I used to refer to these headaches as a Trotskian, on account of feeling like an ice-pick to the skull.4 A Half-Trotsky merely required a pair of sunglasses and I could go about my business, whereas a Full Trotskian made me feel like I was being skewered into the brain. I simultaneously did not see some kind of relationship between myself and having severe headaches. I think I saw them as simply part of the nebulous suffering at that time, and that I was being put through some sort of spiritual trial on account of being a bad person. Well. ‘Girls are cruellest to themselves’.5

Something I struggle with in particular is the lack of language I have as a result of no formal diagnosis. I have reverted to saying things like ‘I’m having a bad episode’ or, ‘I’m struggling’, but it feels so meek, so inadequate. Struggling against what? There is a lacuna where an explanation should be. ‘Lacuna’ with its resemblance to ‘lagoon’. A lagoon of meaninglessness, of lack. I swim around in it, no shore. As Anne Carson describes in The Glass Essay: ‘the cruel illness (pain no words can render)’6 forestalls connection, engendering alienation, perhaps even grief.

Contagious illness is frightening, yes, but its experience is then shared. A A chronic condition emerges in your body, and you never pass it on, it never exits. Huis clos.

ii. Numbers

Woolf goes on:

Yet it is not only a new language that we need, primitive, subtle, sensual, obscene, but a new hierarchy of the passions; love must be deposed in favour of a temperature of 104; jealousy give place to the pangs of sciatica; sleeplessness play the part of villain, and the hero become a white liquid with a sweet taste— that mighty Prince with the moths' eyes and the feathered feet, one of whose names is Chloral.

As anyone who has experienced chronic pain or illness can tell you, the apex of their hierarchy of the passions is a painless existence. This struggle for expression amongst the thorns of pain is the subject of Eula Biss’ essay The Pain Scale. I will also print the opening paragraph in full:

The concept of Christ is considerably older than the concept of zero. Both are problematic—both have their fallacies and their immaculate conceptions. But the problem of zero troubles me significantly more than the problem of Christ.

The organising principle of Biss’ essay is the pain scale— from zero to ten, its function is to illustrate the difficulty in measuring something as subjective, amorphous, and incommunicable as pain. She illustrates the slippage of zero, the starting point: ‘Zero is not a number. Or at least, it does not behave like a number. It does not add, subtract, or multiply like other numbers. Zero is a number in the way that Christ was a man.’7

We think of numbers as having rigidity and immoveable authority in a way which language, with its wily ways, does not. The problem of zero is that it is so easily destabilised— as an anchor of meaning, it is somewhat two-faced and evasive. Biss makes a good point that we have a stronger notion of what Jesus represents than zero. Pain, like colour, is a qualia. To ascribe it a number is therefore difficult work. The problem of qualias is that they are experiential and solipsistic. It is part of the essential boundary between every person that you cannot ever relay, with one hundred per cent accuracy, your experience of, say, the colour red. That boundary— impassable— is the same as the surface of water— fluctuating, always in motion, and therefore impossible to pin down, to make still and identifiable. As Biss points out, ‘A scale of any kind needs fixed points’,8 but if our starting point is zero, our scale begins to waver— to flap like a flag in the wind. It becomes more like a weathervane; it moves. The problem of zero being the starting point also raises some questions. Can zero also not potentially describe immense pain? Is there not something of the abyss, the void, in intense suffering? Biss concludes her essay with a comparison to a different kind of scale, the Beaufort scale: ‘The description of hurricane force winds on the Beaufort scale is simply, ‘devastation occurs’.Bringing us, of course, back to zero.’9

On day six of my headache, I felt I had fallen into zero.

0

A hole.

Trepanning is the process of drilling a small hole into the skull. It is one of the earliest forms of neurosurgery— the practice dates back roughly ten thousand years, making it the oldest known form of surgical intervention.10 It had something of a vogue during the 1960s— John Lennon was keen on it, though never went through with it. The pressure in one’s head during a very bad headache makes the idea of drilling a small hole in there seem kind of fantastic. But that’s what pain will do to you— make you fanciful, wild, desperate. After all, ‘We do not think all philosophy is worth one hour of pain.’11 Indeed, ‘Ignoring the body in the philosopher’s turret’12 is not possible. We ‘cannot separate off from the body like the sheath of a knife… [we] must go through the whole unending procession… until the body smashes itself to smithereens, and the soul (it is said) escapes’.13 Out-of-body experiences are generally quite distressing, even if we think we would like to experience oblivion. Body is home after all.

L’appel du vide is a French term meaning the call of the void. It describes the sensation, for example, of standing on the edge of a cliff and feeling that you want to jump off. It does not necessarily represent suicidality.

Oblivion can be found in both extreme pain and in painkillers. Sometimes, those are your only options, which is a fucker. It forces you into extremes, even if you are quite a mild person.

Mise-en-abyme means ‘placed into an abyss’. It refers to a technique used in both art and literature wherein a work contains a smaller version of itself within the larger whole, such as a story within a story. ‘The Murder of Gonzago’, the play which Hamlet puts on is often used as an example. It can also refer to an infinitely recurring sequence, like a hall of mirrors.14 Pain is analogous to this. It very often recurs in this fashion. Many pain disorders, like fibromyalgia, result from the body developing faulty signals in the nervous system. These signals then become systemised by the brain and central nervous system to repeat. ‘The brain's pain receptors seem to develop a sort of memory of the pain and become sensitized, meaning they can overreact to painful and nonpainful signals’.15 Great.

I read this many years ago on a blog-post. It often comes back to me:

In a 2011 paper on the medical effects of scurvy, author Jason C. Anthony offers a remarkable detail about human bodies and the long-term presence of wounds. “Without vitamin C,” Anthony writes, “we cannot produce collagen, an essential component of bones, cartilage, tendons and other connective tissues. Collagen binds our wounds, but that binding is replaced continually throughout our lives. Thus in advanced scurvy”—reached when the body has gone too long without vitamin C—“old wounds long thought healed will magically, painfully reappear.”

Given the right—or, as it were, exactly wrong—nutritional circumstances, even a person’s oldest injuries never really go away. In a sense, there is no such thing as healing. From paper cuts to surgical scars, our bodies are mere catalogs of wounds: imperfectly locked doors quietly waiting, sooner or later, to spring back open.16

Pain is an accordion. It can concertina down. But it’s there, in stacks, with its cyclical, flighty qualities. It can all be brought back in a single moment.

In Bluets, Maggie Nelson illustrates the problem of the numerical pain scale:

A night I spent in an emergency room in Brooklyn years ago… a young doctor inside asked me to rate my pain on a scale of 1 to 10… I said “6” — he said to the nurse, “Write down “8,” since women always underestimate their pain. Men always say “11”. 17

Biss mentions this as well:

Several recent studies have suggested that women feel pain differently than men. Further studies have suggested that pain medications act differently on women than they do on men… I dislike the idea that our flesh is so essentially unique that it does not even register pain as a man’s flesh does—a fact that renders our bodies, again, objects of supreme mystery.

But here again comes the alienation of pain. And perhaps it is true that men and women experience pain differently. I am prepared to believe it. It certainly corresponds to what I have observed in my life. It is generally the case that if a man is in pain, we will all know about it. Many women suffer in silence. The male loneliness epidemic is very well-documented (and oft-discussed in isolation of their increasingly violent hatred toward women, as though there is no relationship between these things) but it turns out that the loneliest demographic in the UK at least is actually young women, which judging by the incelification of young men, is not exactly surprising. I know many women who experience severe and excruciating pain associated with their menstrual cycles, but do not mention it. But what does this suggest? That men have less resilience, but feel more pain, or that men have more resilience but a greater need for their pain to be recognised? Perhaps the inverse? I couldn’t say. But it certainly appears that pain has a different quality, depending upon who you are. It also, of course, matters a great deal what has happened to you. Some people live relatively pain-free lives.

iii. The headache which has become like a third person. Or: ‘Camilla’ for short. This, I realise, actually makes my boyfriend Diana. Well, he does possess that saintly with a complex interior vibe.

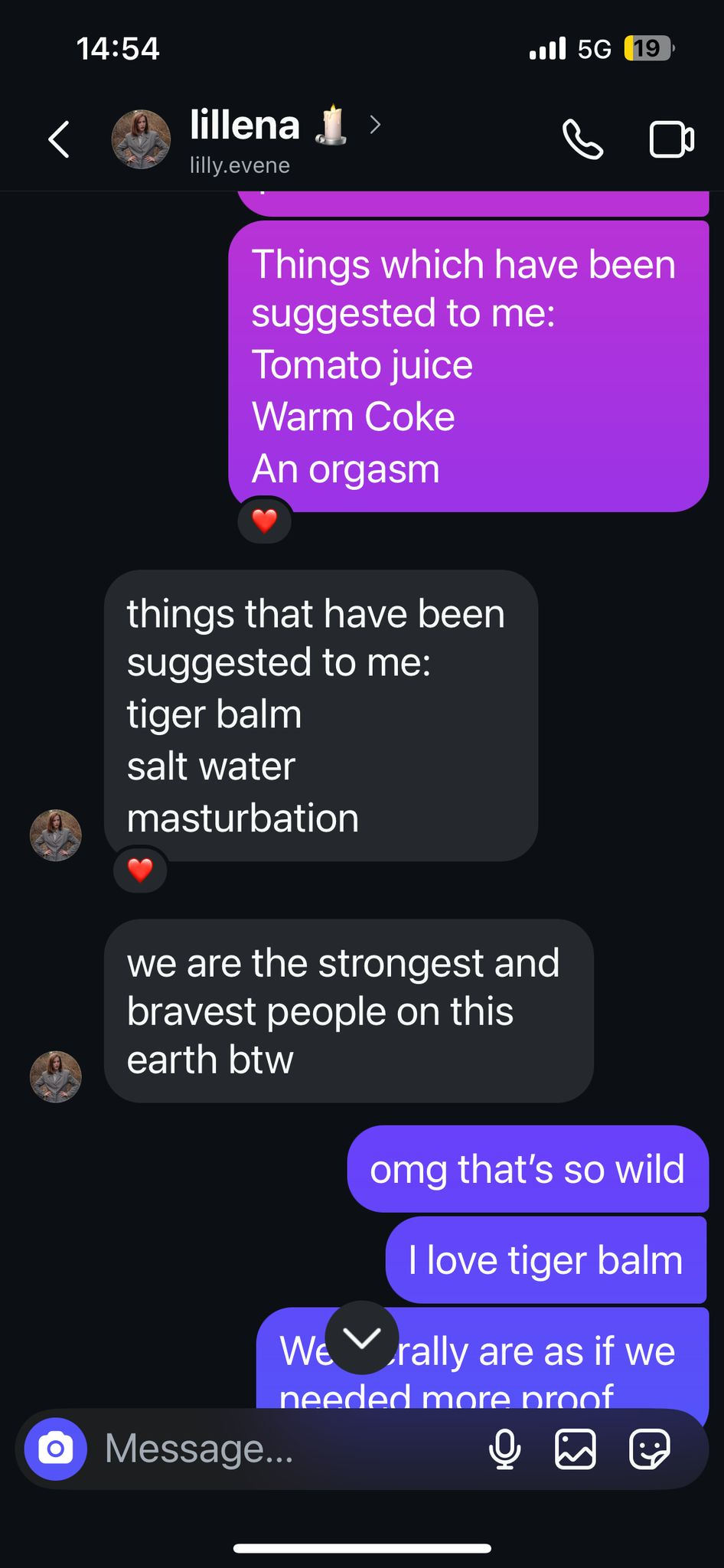

My boyfriend, who is already the most doting man I have ever met (he makes a lot of other boyfriends I know look jack shit) begins to agonise. He is a very calm man. It is one of his distinctive qualities that he is cool as a cucumber; seems unflappable, doesn’t overreact. He is highly rational and carefully considers fact before forming an opinion. But he begins to grow slightly pale with worry and keeps staring at me through his fingers, hands clasped over his mouth. He makes me steak and brings it to me in bed (pictured). He doesn’t leave my side. He makes trips up and down the stairs for ice. He brings me ice water, diet coke, shots of lemon juice, at one point just a snack plate of some of my favourite things: anchovies, salt and vinegar crisps, blue cheese, green olives, dark chocolate. He runs me a bath, puts me in it. He presses on the pressure points in my head, he massages my jaw, he rubs my feet. He turns all the lights down low. He offers to read to me. A friend of mine and I trade analgesic suggestions (the witchier and more deranged the better) we have received (also pictured), which includes tomato juice, warm coke, a tight band around the head, salt water, tiger balm, an orgasm (not necessarily in that order). We try them all.

I take codeine for severe period pain, but it wasn’t touching the sides. And you can’t take it for more than three days anyway, so I had to cash out. I’ve fought tooth and nail for my life to be Cool and Good. I had some very dark times back there. So I’m quite careful, now, and try to be judicious. I don’t need an opioid addiction!

This was day three, I believe. Sounds ridiculous maybe but it was actually moving that he was so accurate. So many of my favourite things! I have a very briny, salty palette. I’ll happily eat anchovies out of the tin, and I take my martinis filthy.

Day five? We wondered if I was just very anaemic. It was delicious, and made me feel better by virtue of making me feel loved. Also: he has a genuine talent in the kitchen. I have eaten better during this last year than I ever have in my life.

Genius to genius mind transmission

Back to Woolf for a moment. We cannot all be a bleeding heart according to her. An endless stream of tears would only drown us.

But sympathy we cannot have. Wisest Fate says no. If her children, weighted as they already are with sorrow, were to take on them that burden too, adding in imagination other pains to their own, buildings would cease to rise, roads would peter out into grassy tracks; there would be an end of music and of painting; one great sigh alone would rise to Heaven, and the only attitudes for men and women would be those of horror and despair.18

If we all cried over every headache, nothing else would get done. But is there not some comfort in the world still turning— in the sound of the vacuum in the next room, in warm food being prepared and brought to you through your patient-door, in fresh linens on the bed, in glorious daytime television?

Human beings do not go hand in hand the whole stretch of the way. There is a virgin forest, tangled, pathless, in each; a snow field where even the print of birds ' feet is unknown. Here we go alone, and like it better so.

This reminded me of the lyrics in the Christian folk song ‘You’ve Got to Walk’: ‘You’ve got to walk that lonesome valley… Nobody here can walk it for you, you’ve got to go there by yourself’. I can’t say exactly why I was so stunned by this piece of music; I was introduced to it via the video game Kentucky Route Zero during, as it happens, an episode of illness. Whether it was the fever intensifying the potency of the song, it tempted me to become religious.

I close my eyes and I imagine the snow field, with its white planes, lunar and bridal.

The trouble was not simply that I had a headache but I was white as a sheet and was staring out of disconcertingly hollow eyes. My mother has a phrase she uses when she’s tired: ‘My eyes look like two piss-holes in the snow.’ I have always found this hilarious. Now it was my turn. My eyes had gone dark and small, partially because it bothered me to open them all the way. The pain was tectonic; all cruelty. Sometimes a high, shrill wind was whipping above my head, at other times I imagined my skull as great plates, glaciating, groaning. Like standing on Earth looking up at the moon gleaming cold, clean, and pure, her remoteness the remoteness of health— ‘We [are] able… to look, for example, at the sky’19. At a certain point, you start to believe that this is your life now. I could not envision an end to the pain: it had become polyphonic and total.

On day six, I became genuinely concerned. I started to think I might have to go to hospital— I felt certain that something was gravely wrong. I had slipped into a fugue-like state. The whole world was blurry and I was feeling ghastly and morbid. E and I had gone for a walk and we decided I should ring the GP— I had an appointment booked for the Friday and I asked if they could see me that day. They found a slot for me and we went straight there. In my own head I had been half-telling myself that it wasn’t so serious, it was somehow my fault for not being hydrated enough or conscientious enough and I have bad posture anyway. She diagnosed me with chronic migraines. She wrote me up a prescription. I have become extremely resistant to going to the doctors for any reason in recent years. But the feeling, this time, of being so assiduously listened to, of being believed, was euphoric. And to receive an answer so immediately helped me to accept that what I had been experiencing was real.

I realised then, to a greater degree, why it is called care. Good, genuine care is wonderful. I relaxed into the reality of things— both in the sense that my strange and amorphous experience had a name, and also that it had limits and could be treated.

E took me home and put me in bed with water and a diet coke. When my prescription was ready to pick up, he went and fetched it for me. The following day, after a very long chemical sleep, the headache had cleared. For now, I was free.

It took me another week to fully return to myself: the experience had been draining and estranging. The world had continued to revolve, it felt, without me. Walking around the next day felt surreal: sounds were a little too loud, everything was just slightly abrasive and unfamiliar. I felt vulnerable and child-like walking through town, and I hung onto E’s arm a little tighter than usual, half-hiding behind his shoulder. But the sun had come out and was warming my skin. We ate breakfast in the garden, we bought books from the second-hand place, we fixed my desk, we went to the cinema, we talked all night. We went back to living our life that I love so much.

Despite the intensity of this individual episode, I am actually far better now than I was in the past. The shrapnel doesn’t always come out. It does fit you with this… nostalgia for parts of your life not lived, a sweet agony which is both grief for what was taken from you and a gratitude that it’s not fucking going on anymore. Life, yes, sometimes seems a bit banal without some constant weather front of shrieking orchestral agony rolling in, wave on wave, but actually the banality is peace. And though sometimes I miss the novel ways I was able to think about things, I would never trade places with my younger self. It was through her determination and dauntless hope that I can report on one very bad week as a novelty.

Trying to force pain through the filter of language is a task I will probably have to tend to throughout my life. I often find 1984 to be an unlikely source for such a penetrating line about romantic life but, to be loved is to be understood, and I recognise the richness this brings to my life.

I want to end with this from Anne Carson:

‘Nor would the mechanical death of moments have come roaring down on us as darkness, had we not stopped to look round for the light’.

Thank you for reading! I write posts fortnightly! (I do now). Consider subscribing if you have not already.

Until next time,

— M

Anne Carson, Plainwater

Virginia Woolf, On Being Ill

Woolf

Trotsky was assassinated with an ice-axe which sadly pierced his brain.

Anne Carson, The Glass Essay, Glass and God, Cape Poetry,

Carson

Eula Biss, The Pain Scale

Biss

Biss

Charles C. Gross, A Hole in the Head: A History of Trepanation

Pascal, Pensees

Woolf

Woolf

Marcus Snow, Into The Abyss

https://repository.londonmet.ac.uk/1106/8/SnowMarcus_IntoTheAbyss_NoGifImages.pdf

Mayo Clinic: Fibromyalgia

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/fibromyalgia/symptoms-causes/syc-20354780

Maggie Nelson, Bluets

Geoff Manaugh, Black Maps: American Landscape and the Apocalyptic Sublime, Steidl, 2013

Woolf

Woolf